Ross Bonander

The Hockey Writers

Ross Bonander

The Hockey Writers

1496

Reads

0

Comments

Stem Cell Treatment and the Exploitation of Mr. Hockey

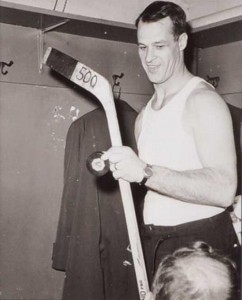

No. 9 Gordie Howe has always been something of an outlier.

His frame was made for hockey: Short, powerful legs gave him a low center of gravity and made him almost impossible to knock off his skates. He was an uncommon athlete who blasted baseballs over the fence at Briggs Stadium; a scratch golfer who once shot 75 with a fractured foot; a hockey player who needed just one hand on his stick to score top-shelf from the hash marks—and it didn’t matter which hand.

He is the greatest hockey player of hockey’s golden era.

I’m a Gordie Howe fan. A fan of the style of hockey he played. And I’m especially a fan of Gordie Howe stories. They are the best hockey stories.

I’ll gladly take almost any sourced Gordie story and write it into a narrative as gospel, doing my small part to grind anecdotes into history. I might even add a detail, like I did in the first paragraph above: In his book Gordie Howe’s Son, Mark Howe tells of watching Gordie stand at the hashmarks and fire pucks under the crossbar with only one hand. Since Gordie was known to be ambidextrous, I added that “it didn’t matter which hand” because it sounded good.

In other words, I have always bought into the legend. Drank the Kool-Aid.

I will continue to do so as it relates to hockey. But the latest developments regarding an experimental treatment in Mexico for ischemic stroke go beyond what I’m willing to buy into.

In Case You Missed It

Mainstream reporting of Gordie Howe’s enrollment in a stem cell clinical trial back on 19 December turned out to be mostly misinformation, which I will address in a moment. What does not appear to be misinformation is that in December Gordie had, in the words of his son Murray, one foot in the grave, and now, he’s making a recovery.

That’s the great part of this. And for many people, that’s all that matters.

But for others, in particular those in the research and medical communities as well as those people seeking treatments for life-threatening or chronic illness, the not-so-great part of this matters at least as much, if not much more.

Recap

Prior to 8 December, Gordie’s health was deteriorating due to dementia complicated by at least one ischemic stroke. His loved ones worried that his time was near. Then the family was approached by executive members of a San Diego-based company called Stemedica, among them a former employee of the Detroit Red Wings, David McGuigan. Aware of Gordie’s condition, they suggested that perhaps the adult stem cells they developed and manufactured might be helpful to him since at least one experimental treatment involves donated stem cells for use in patients who have suffered ischemic stroke.

Clinical trials using Stemedica stem cells are being conducted in the United States, Mexico, and elsewhere, so it was arranged for Gordie to undergo treatment in Tijuana, Mexico by company partner Novastem. On 8 December the Howes traveled to Tijuana where Gordie received two types of adult donor stem cells, mesenchymal stem cells and neural stem cells, as part of a clinical trial.

On 19 December, the Howe family issued a press release that included many of these details and boldly noted that Gordie’s health had improved dramatically. The release publicly named the companies involved in providing the stem cells and the treatment, even though as a clinical trial participant—as a patient— Gordie’s anonymity was protected.

On 16 January Bob Duff reported in the Windsor Star that Dr. Murray Howe, Gordie’s youngest son, told him that immediately following the procedure for receiving neural stem cells (administered intrathecally, into the spine followed by eight hours rest) Gordie was already improving, using more words when he spoke and walking to the bathroom on his own power.

Murray, a radiologist and the de facto family spokesman on Gordie’s health status, said it was “almost a biblical moment” for him to witness that. He later said that his father’s continued recovery left him astonished, and that he had “never seen anything like it in medicine.”

Red Flags

Bradley Fikes, a reporter for the San Diego Union-Tribune was among the first to suggest that something wasn’t right. He reached out to David Gorski of Science-Based Medicine, and soon a whole set of holes were uncovered in the story that had been fed to the public, including some rather dubious ethical issues. Gorski’s elegantly written posts, “Stem cells versus Gordie Howe’s stroke, part 1 and part 2” pointed out several major problems with the information provided by the family.

Among Gorski’s issues was the fact that nobody could find any published information on a clinical trial being conducted by Novastem. This was a major red flag. Clinical trial protocol involves publication of the design of that trial prior to recruitment on an official database such as clinicaltrials.gov. Also, the company needs to recruit patients; failing to publish information about the trial is going to make it very, very hard to recruit anybody.

Among Gorski’s issues was the fact that nobody could find any published information on a clinical trial being conducted by Novastem. This was a major red flag. Clinical trial protocol involves publication of the design of that trial prior to recruitment on an official database such as clinicaltrials.gov. Also, the company needs to recruit patients; failing to publish information about the trial is going to make it very, very hard to recruit anybody.

Gorski’s posts appeared to elicit a press release by PR firm The Townsend Team, which announced—on Christmas Eve no less and in an email Gorski received—that Novastam had initiated treatment of its first patient in a study of stem cells and ischemic stroke.

This patient is without a doubt Mr. Hockey.

This means the clinical trial Gordie was alleged to have been a part of did not appear to exist when he entered it; it only came to life after skeptics raised alarm bells.

Furthermore, Stemedica is conducting a clinical trial of its stem cells in patients with ischemic stroke right here in the United States. Why not save Gordie the trip to Mexico and enroll him stateside? Because due to the timing of his stroke, Gordie was ineligible to participate in that trial. As it turns out, he was also ineligible to participate in the one he appears to be participating in as well, for the same reason.

Currently, thousands travel from the US to Tijuana for experimental stem cell treatments. This is legal. However, they are often lured in by claims asserting the ‘curative power’ of stem cells, and typically pay upwards of $30,000.

Yet, as regards ischemic stroke and neural stem cell infusions, Dr. Larry Goldstein (Distinguished Professor, Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, Department of Neurosciences, Director of the UC San Diego Stem Cell Program, and Director of the Sanford Stem Cell Clinical Center, at the UCSD School of Medicine) told me that there is a large gap between what is known about stem cell therapy and what is claimed it can achieve.

“I am not aware of any established, effective treatments of brain injury from stroke using adult neural stem cells,” said Goldstein, who was not commenting specifically on either Stemedica or Gordie. “The problem is, when you inject these stem cells into a patient’s spine, there is currently no way for you to know, or for you to control, what area of the body those stem cells will migrate to. Ideally they would migrate to the site of the injury, but they might go anywhere. And as long as the patient is alive, there is no way to know where those neural stem cells actually went.” Only by going into the brain post-mortem can you find that crucial information.

This complicates objective conclusions about the success of a treatment while that patient is alive. More subjective clinical measurements might hint at success, but other factors can’t be excluded. As Gorski notes,

[J]ust before he went to Tijuana, [Gordie] had been hospitalized for dehydration that had rendered him unresponsive. Before that, he had had a rough November … Indeed, if you look at the news coverage of Howe’s condition since October 26 [the date of his stroke], you’ll see reports of rapid recovery mixed with reports of setbacks. It’s clearly been a bit of a rollercoaster ride, which makes it very hard to tell if any improvement is due to anything other than the nature the stroke, or if it’s durable … Given Howe’s fluctuating, but overall slowly-improving condition, it’s hard to attribute his current condition to the stem cell treatment.

According to anecdotal information from patients receiving Stemedica’s cell lines at other clinics, three months or more must pass after infusion before doctors will determine treatment success (recall Murray’s reaction to his father’s condition first occurred just hours after administration). Nonetheless, patients report being asked to record glowing video testimonials for these hospitals before they even check out.

Dr. Hockey

With Gordie’s fragile health making news, Murray Howe has come to the attention of the public for the first time, at least compared to his mother or to his hockey-playing brothers Mark and Marty. Following the skepticism expressed online, Murray went on the offensive, supporting Stemedica, saying that stem cell therapies have been proven effective, and asserting his own ability to oversee the neurological treatment of his dad despite being a radiologist (and despite it being considered unwise for any doctor to treat his or her family members). Most tellingly however was what Murray said when it was revealed that Gordie’s treatment was on the house:

Did Novastem treat our father for free? You betcha. They were thrilled and honored to treat a legend. Would you charge Gordie Howe for treating him? None of his doctors ever do.

This is a trope familiar to hockey fans, one that supplies the subtext for virtually every major story about Gordie since his first retirement from the NHL: how egregiously the Detroit Red Wings exploited, underpaid, and lied to Gordie during his celebrated hockey career. And further, how Gordie, led by the business acumen of his late wife, went on a barnstorming promotional tear when his career was over, squeezing every last penny out of his fame, all in the name of cashing in on Mr. Hockey (and contributing to children’s charities).

Back in the day, the Red Wings assured Gordie that he was the highest paid player in the league. In the late 1960s, shortly before his first retirement, Gordie had lunch with Bobby Baun, a defenseman Detroit picked up from the Oakland Seals. Baun—a decent veteran best known for scoring an overtime playoff goal for the Toronto Maple Leafs on a broken ankle—informed Gordie that the Wings had signed him to a contract that paid him double what Gordie was making.

“That hurt,” Gordie said. “I can tell you, that hurt.” [1]

Understandably, Gordie (and others from the era) were furious to learn just how badly their teams had been screwing them over. It was around the time of his retirement in 1971 that Gordie, led by wife Colleen, began a never-ending Gordie Howe promotional tour that has included its share of cringe-inducing promos, ranging from his brief appearance in an IHL game in the 1990s so that he could claim to have played pro hockey in six different decades to securing the trademarks for both Mr. Hockey, and, for Colleen Howe, Mrs. Hockey. But hey, everyone else was making a buck off Gordie, surely he was entitled to some of those riches.

Thus, this latest stunt—attaching the man’s name to a proprietary biotechnology product which its developers are attempting to position for market approval by the US Food and Drug Administration in the near future—really starts to feel like only the latest stop on that promotional tour, now with Murray leading the way. (The trademark for Dr. Hockey is at the moment available in Canada and the US).

This tie-in won’t result in the sale of a few extra replica jerseys, but it might result in inspiring other patients to flock to Tijuana for experimental treatment. This would be fine—even great considering the low number of eligible adults who take part in clinical trials—except there is no reason for anyone in the research or medical community to believe that many of these trials are being conducted according to rigorous scientific standards.

If we are to have treatments available to us that are safe and effective, they must first be subjected to uncompromising science. A major treatment such as adult stem cells for stroke demands that the method of treatment be described in a peer-reviewed scientific journal and that it be tested across rigorously controlled multiphase clinical trials which would explore the safety, tolerability and efficacy of the treatment in as many people as possible.

“When I think about the potential of stem cell therapy twenty years from now, it’s impossible not to get excited,” said Goldstein. “The promise held by stem cells in treating an array of different medical conditions is incredibly tantalizing. But I also know first-hand how much work must be done before we get there.”

In hockey, No. 9 Gordie Howe was an outlier, special and unique in every imaginable way. In medical research, he can still be an outlier, but in order for his contribution to count, he cannot be Mr. Hockey getting stem cells, or the legendary No. 9 in a clinical trial. He must only be an 86 year-old male with a history of stroke whose participation in a clinical trial yields data broadly useful to ongoing research. Otherwise he’s just another celebrity whose personal illness is transformed into commodity.

End Notes

1. Willes, Ed. The Rebel League: The Short and Unruly Life of the World Hockey Association. McClelland and Stewart; 2004.

I urge all interested readers to check out David Gorski’s two posts at Science-Based Medicine:

Stem cells versus Gordie Howe’s stroke

Stem cells versus Gordie Howe’s stroke, part 2

Popular Articles

Blackhawks Chicago

Blackhawks Chicago Panthers Florida

Panthers Florida Penguins Pittsburgh

Penguins Pittsburgh Rangers New York

Rangers New York Avalanche Colorado

Avalanche Colorado Kings Los Angeles

Kings Los Angeles Maple Leafs Toronto

Maple Leafs Toronto Bruins Boston

Bruins Boston Capitals Washington

Capitals Washington Flames Calgary

Flames Calgary Oilers Edmonton

Oilers Edmonton Golden Knights Vegas

Golden Knights Vegas Flyers Philadelphia

Flyers Philadelphia Senators Ottawa

Senators Ottawa Lightning Tampa Bay

Lightning Tampa Bay Red Wings Detroit

Red Wings Detroit Islanders New York

Islanders New York Sabres Buffalo

Sabres Buffalo Devils New Jersey

Devils New Jersey Hurricanes Carolina

Hurricanes Carolina Stars Dallas

Stars Dallas Jets Winnipeg

Jets Winnipeg Blue Jackets Columbus

Blue Jackets Columbus Predators Nashville

Predators Nashville Wild Minnesota

Wild Minnesota Blues St. Louis

Blues St. Louis Mammoth Utah

Mammoth Utah Ducks Anaheim

Ducks Anaheim Sharks San Jose

Sharks San Jose Canucks Vancouver

Canucks Vancouver