Steve Beisswanger

The Hockey Writers

Steve Beisswanger

The Hockey Writers

29

Reads

0

Comments

World Juniors: The Evolution of a National Obsession

The voice in the promotional spot for the upcoming International Ice Hockey Federation (IIHF) World Junior Championship (WJC) says in a deep matter-of-fact voice that “before the spotlight, before they are legends, they played in the World Juniors.” Using images of Wayne Gretzky and Sidney Crosby to get the point across, the commercial is intent on building excitement around the 2020 edition of the tournament to be played in the Czech Republic from Dec. 26 to Jan. 5.

The tournament has now become a holiday-period television tradition in hockey-loving families across Canada. Every year, it showcases the best players under 20 years old. For many of these players, the tournament is the opening chapter of their hockey stories.

In a book entitled Road to Gold – The Untold Story of Canada at the World Juniors (published by Simon & Schuster), Mark Spector, a journalist for Sportsnet, traces the evolution of how a once modest junior-level hockey tournament became the significant multi-million dollar sports property that it is today.

The book offers some interesting historical elements about how the tournament emerged and grew. Spector also uses a number of compelling personal narratives and stories from players who have worn the Team Canada jersey during the Christmastime tournament. The reader will discover insightful contrasts between very different hockey journeys.

There are players for whom the tournament was the launchpad to famed careers. For others, whose images are not seen in the commercial, the tournament was the pinnacle of a career spent struggling on the margins of professional hockey.

Many hockey fans around the world are getting ready to celebrate the holiday period with family by decorating their homes, trimming Christmas trees and wrapping gifts. But for a group comprised of the best young hockey players in the world, their priority is the intense preparation required to proudly represent their respective countries with the hope of bringing back home a gold medal.

As we eagerly anticipate the drop of the puck to start the 2020 edition of the tournament, here are some of the highlights from Road to Gold that provide us with the back story, history and context that led to the games we are anxiously going to enjoy.

We Have to Do Something

Spector opens the book with Murray Costello, then-president of the Canadian Amateur Hockey Association (CAHA), waiting in a lobby at the Skyline Hotel in Ottawa in 1981. He wanted to meet with the powerbrokers of Canadian junior hockey who were gathered for their annual general meeting. He had an idea to address Canada’s performance at a yearly tournament originally started in 1974 that matched the best under 20-year-old hockey players from the Soviet Union, Czechoslovakia, Sweden, Finland and the United States.

Since its inception, the tournament had been dominated by the Soviet Union. Canada’s entry in the competition was the Memorial Cup winner from the previous season complemented with additional last-minute picks. The catalyst for Costello’s angst was sparked by Canada’s 7-6 loss to West Germany in the Consolation Round leading to a seventh-place finish in 1981.

When Germany beat Canada with Dale Hawerchuk on the team, I thought, that’s just not fair to him, and it’s not fair to Canada. We have to do something.

Comment from Murray Costello, then-president of the CAHA in Road to Gold, p. 5.

As head of the regulatory body that was the precursor to Hockey Canada, Costello wanted to set up an all-star team of the best Canadian junior players and borrow them for the Christmastime tournament. That was his pitch to the reluctant owners of the junior teams who were less than receptive at the idea of losing their best players during a critical part of the season.

Costello was persistent and, especially, well prepared. He had previously secured seed funding from Sport Canada (an entity of the Federal Government) with a well-thought-out plan to develop the best young Canadian players at the under-18, under-20 and Olympic levels. Part of his overall plan was a more strategic approach to selecting and preparing a true national junior team to play and successfully perform at the international level. He successfully overcame the reluctance of the team owners and executives and his efforts ultimately took shape as the Program of Excellence.

Breaking the Soviet Stranglehold

The benefits of the new program would be put to the test in the 1982 tournament being held jointly in Canada (Winnipeg and Kenora) and the United States (Bloomington, Minneapolis and Duluth). The inaugural head coaching duties were assigned to Dave King. He would have the responsibility to prove the worth of a national approach to selecting young hockey talent for competition against the best junior players from around the world.

The Soviet Union had won seven of the first eight tournaments (from 1974 to 1980). They were the dominant force. The team practiced, played and lived together all year long. For Team Canada, their game against the Soviets in Winnipeg was going to be a significant test of the infant Program of Excellence. The stakes were high as the game was also broadcast on television to the entire country.

Unexpectedly, Canada beat the Soviets 7-0 in front of a jubilant home crowd. Spector writes that the win “blew wind into the sails of the whole Program of Excellence concept” (p. 33, Road to Gold). Canada also won their first gold medal at the WJC in 1982. The foundation was now set, the model established. Spector goes on, “It was on the shoulders of this team that the future of the Program of Excellence would rest, and if this much could be accomplished on the first try, who knew what this program could accomplish in the next decade” (p. 39, Road to Gold).

Changing Perception of the Game

One of the most interesting elements in Spector’s book is how he parallels the evolution and growth of the WJC with changes to how the game was being perceived in Canada. The new approach to player selection and development was clearly paying dividends on the ice. In the decade following the 1982 gold medal and the maiden test of the Program of Excellence, Canada was on the podium six times, including being on the highest step on four occasions (1985, 1988, 1990 and 1991).

Team Canada 1983-1992

- 1983: Bronze (Gold: Soviet Union) – Host: Leningrad, Soviet Union

- 1984: Forth (Gold: Soviet Union) – Norrköping and Nyköping, Sweden

- 1985: Gold – Helsinki and Turku, Finland

- 1986: Silver (Gold: Soviet Union) – Hamilton, Ontario

- 1987: disqualified (Gold: Finland) – Piestany, Czechoslovakia

- 1988: Gold – Moscow, Soviet Union

- 1989: Fourth (Gold: Soviet Union) – Anchorage, Alaska

- 1990: Gold – Helsinki and Turku, Finland

- 1991: Gold – Saskatoon and Regina, Saskatchewan

- 1992: Sixth (Gold: Commonwealth of Independent States – former Soviet Union) – Füssen and Kaufbeuren, Germany

However, this period of time is also remembered for a more violent incident that occurred during the 1987 tournament in a game between Canada and the Soviet Union. The bench-clearing brawl that occurred is notoriously known as the “Punch-up in Piestany”. Much has been written about the incident. It has been the topic of a book and numerous television documentaries.

Spector dedicates an entire chapter to the incident. It is a justified approach considering the impact it had on how Canadians were perceiving the game. The incident became a catalyst for reactions within and outside of the hockey community.

This had become a seminal moment. An important intersection in Canadian hockey culture, where “old-time hockey” ran smack into a populace that had finally decided to question why our young men were being thrown out of a tournament for bare-knuckle brawling. A growing number of people were no longer comfortable with our favorite sport playing out as if it were in some swinging-doors bar in an old Western movie, especially when it was our youngest who were being exploited.

On the impact of Piestany, excerpt from Road to Gold, p. 58.

Following the proverbial black eye suffered by Canada’s disqualification from the 1987 tournament, the Program of Excellence continued to propel the country’s team to success. Team Canada rebound with gold medals in 1988 and 1990. There was a growing interest in the high caliber of junior hockey being played during this festive time of the year.

The TSN Turning Point

This heightened level of awareness was also occurring at a time when specialized television channels were now offering viewers content tailored to their specific likes and preferences. The Sports Network (TSN) was growing in popularity but was still a fringe channel with little compelling content, meagre ratings and a tight budget. Following a change in policy by the federal broadcasting regulator, TSN was allowed to move to basic cable which instantaneously increased its potential audience fivefold. The network now needed good content to fill its airwaves.

As the rights to the WJC were becoming available, the timing was right for TSN to acquire an affordable sports property. It signed a five-year deal with the CAHA. The big reveal would be the 1991 tournament held in Saskatchewan. In terms of exposure, it was a win-win for both TSN and Canadian hockey.

From an exposure perspective, everything changed with that 1991 tournament in Saskatoon. Suddenly, the tournament was truly a sensation coast to coast, and, coupled with the fact that most every province has a tie to at least one player, newspapers across Canada had sent reporters not only to cover the tournament, but to report on the exploits of “their guy” on Team Canada.

On the impact of the TSN deal, excerpt from Road to Gold, p. 105.

The good fortune was not limited to the boardroom. On the ice, Team Canada won its first tournament on home soil. TSN quickly discovered that viewers across Canada were identifying with the maple leaf on the jerseys of their national junior team. The WJC was now becoming a prime sports property that could command significant advertising dollars and revenues from broadcasting rights.

Building a Business

Team Canada’s success on the ice was the perfect ingredient to keep building exposure and excitement about the tournament. With a string of five consecutive gold medals from 1993 to 1997, the WJC was becoming synonymous with Canadian success.

Team Canada 1993-2002

- 1993: Gold – Host: Gävle, Uppsala and Falun, Sweden

- 1994: Gold – Ostrava and Frýdek-Místek, Czech Republic

- 1995: Gold – Red Deer, Edmonton and Calgary, Alberta

- 1996: Gold – Boston, Amherst and Marlborough Massachussetts

- 1997: Gold – Geneva and Morges, Switzerland

- 1998: Eight (Gold: Finland) – Helsinki and Hämeenlinna, Finland

- 1999: Silver (Gold: Russia) – Winnipeg, Brandon and Selkirk, Manitoba

- 2000: Bronze (Gold: Czech Republic) – Skellefteå and Umeå, Sweden

- 2001: Bronze (Gold: Czech Republic) – Moscow and Podolsk, Russia

- 2002: Silver (Gold: Russia) – Pardubice and Hradec Králové, Czech Republic

A merchandising deal (with Nike in 1999) and a move away from the round-robin-only format to a playoff-style tournament (in 1996) brought both more money and added drama to an increasingly popular and successful enterprise.

The promotional spots one sees today on television eliminate any illusion that the WJC is now, in fact, big business. In 2014, TSN and Hockey Canada (CAHA and Hockey Canada merged in 1998) signed a new television deal estimated at $20 million annually (Road to Gold, p. 106).

Journeys to Different Destinations

Another interesting contrast in the book is the different paths taken by players who played in the WJC. The composition of the 2005 team is considered to be the best Canadian entry ever. With names such as Sidney Crosby, Patrice Bergeron, Ryan Getzlaf, Jeff Carter and Shea Weber, it is of little surprise that the team dominated the tournament going undefeated and winning the gold medal.

While the tournament was a preview of the talent many of these players would bring to long and successful careers in the NHL, for others the WJC was the summit of careers spent on the margins of hockey glory. Spector outlines the path of Jeff Glass, the goalie on the gold medal team of the famed 2005 edition of Team Canada and Justin Pogge, the goalie for the gold medal winning team in 2006. Following their respective success at the WJC, their careers were spent moving between minor league teams.

Spector accurately captures the reality faced by such players. “It’s always going to be a journey, but what we never know is where that journey will lead. For some, the World Juniors is a stepping stone; for others, it’s the peak. But for all of them, it’s a memory that never gets old” (Road to Gold, p. 181).

The Perversion of Pressure

Over the years, Canada has won 17 gold medals at the WJC. This has led to an incredibly high level of expectations placed every year on a new group of teenagers who have the privilege of representing Canada on the world hockey stage. The advertising money and the NHL-size rinks filled to capacity create a backdrop where there is a very high level of pressure to win. This is significantly compounded by what Spector describes as: “The gold or bust expectation that Hockey Canada itself once thought was too much, but today is resigned to” (Road to Gold, p. 195).

It is therefore of little surprise that the high expectations of success showed its ugly side when Team Canada captain and Anaheim Ducks prospect Maxime Comtois missed a penalty shot in overtime during the quarterfinals against Finland in 2019. Canada ultimately lost the game and finished the tournament in sixth position. Social media was vicious in its critique of Comtois.

Notwithstanding the ugliness of the treatment suffered by Comtois in the aftermath of Canada failing to win gold in 2019, there is a polarized debate within the hockey community itself about the enormous pressure placed on these young players. Spector quotes former NHL goalie Roberto Luongo who played in the WJC in 1999 when Canada lost the gold medal in overtime.

In referring to Comtois, Luongo says: “Sometimes, everybody has got to just take a little bit of a step back. It’s hockey, it’s a tournament that we all want to win, but we’ve just got to realize that these are kids, and they’re trying the best that they can to represent their country well. I’m sure that the kid was more heartbroken than anyone else was.” (Road to Gold, p. 191).

The alternate view contrasts significantly with Luongo’s perception. Spector writes that, among Team Canada alumni, there is “unilateral agreement that the pressure we put on Canadian kids is not too much.” He adds that, “You simply cannot find a successful hockey person who would shield our elite teenagers from that spotlight” (Road to Gold, p. 198).

The debate might well be unresolvable. Luckily for Comtois he has made the most out of the situation and has become a passionate advocate for an online anti-bullying campaign in partnership with one of the main corporate sponsors of the WJC.

Team Canada 2003-2019

- 2003: Silver (Gold: Russia) – Host: Halifax and Sydney, Nova Scotia

- 2004: Silver (Gold: United States) – Helsinki and Hämeenlinna, Finland

- 2005: Gold – Grand Forks and Thief River Falls, North Dakota

- 2006: Gold – Vancouver, Kelowna and Kamloops, British Columbia

- 2007: Gold – Leksand and Mora, Sweden

- 2008: Gold – Pardubice and Liberec, Czech Republic

- 2009: Gold – Ottawa, Ontario

- 2010: Silver (Gold: United States) – Saskatoon and Regina, Saskatchewan

- 2011: Silver (Gold: Russia) – Buffalo and Lewiston, New York

- 2012: Bronze (Gold: Sweden) – Calgary and Edmonton, Alberta

- 2013: Fourth (Gold: United States) – Ufa, Russia

- 2014: Fourth (Gold: Finland) – Malmö, Sweden

- 2015: Gold – Toronto and Montreal

- 2016: Sixth (Gold: Finland) – Helsinki, Finland

- 2017: Silver (Gold: United States) – Montreal and Toronto

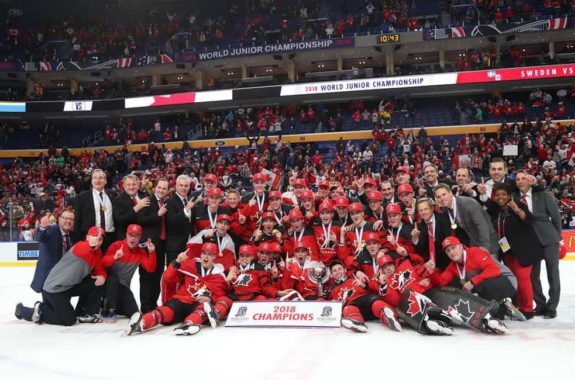

- 2018: Gold – Buffalo and Orchard Park, New York

- 2019: Sixth (Gold: Finland) – Vancouver and Victoria, British Columbia

Some of the players we will see in the 2020 edition of the WJC will go on to have successful careers in the NHL. Some might, one day, be inducted to the Hockey Hall of Fame and forever be considered as a legend of the game.

As fans, we get to watch the opening chapter of hockey careers that will take very different directions. We are watching hockey history unfold. That is maybe one of the main reasons why this tournament has become the significant and successful hockey event that it is today. In that regard, Spector’s book is a great primer on how we got here.

The post World Juniors: The Evolution of a National Obsession appeared first on The Hockey Writers.

Popular Articles

Blackhawks Chicago

Blackhawks Chicago Panthers Florida

Panthers Florida Penguins Pittsburgh

Penguins Pittsburgh Rangers New York

Rangers New York Avalanche Colorado

Avalanche Colorado Kings Los Angeles

Kings Los Angeles Maple Leafs Toronto

Maple Leafs Toronto Bruins Boston

Bruins Boston Capitals Washington

Capitals Washington Flames Calgary

Flames Calgary Oilers Edmonton

Oilers Edmonton Golden Knights Vegas

Golden Knights Vegas Flyers Philadelphia

Flyers Philadelphia Senators Ottawa

Senators Ottawa Lightning Tampa Bay

Lightning Tampa Bay Red Wings Detroit

Red Wings Detroit Islanders New York

Islanders New York Sabres Buffalo

Sabres Buffalo Devils New Jersey

Devils New Jersey Hurricanes Carolina

Hurricanes Carolina Stars Dallas

Stars Dallas Jets Winnipeg

Jets Winnipeg Blue Jackets Columbus

Blue Jackets Columbus Predators Nashville

Predators Nashville Wild Minnesota

Wild Minnesota Blues St. Louis

Blues St. Louis Mammoth Utah

Mammoth Utah Ducks Anaheim

Ducks Anaheim Sharks San Jose

Sharks San Jose Canucks Vancouver

Canucks Vancouver