Thw Archives

The Hockey Writers

Thw Archives

The Hockey Writers

28

Reads

0

Comments

The NHL’s Evolution of Integration

In honor of Black History Month, a closer look at how black players have helped progress the game of hockey is in order. It has been 60 years since Willie O’Ree played his first game in the NHL, but his legacy has never been more important. As of Feb. 1, there have been 23 players who are either black or biracial who have played in the NHL this season (as of 2017-18 season).

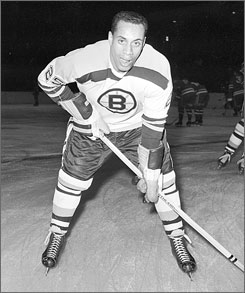

Willie O’Ree: Breaking Through the Wall

Jackie Robinson crossed into history by becoming the first black athlete to play in an MLB game in 1947; Kenny Washington and Woody Strode played in the NFL in 1946; Earl Lloyd made his first NBA appearance in 1951, but it wouldn’t be until 1958 that the first black athlete played in the NHL.

Willie Eldon O’Ree was born on Oct. 15, 1935 in Fredericton, New Brunswick, Canada. As a young man, he played his youth hockey in Fredericton for the Falcons, Merchants, Jr. Capitals, and Capitals before moving on to playing for the Quebec Frontenacs (1954-55) and Kitchener Canucks (1955-56). O’Ree started playing for the Quebec Aces in 1956, but his most memorable moments with the Aces weren’t in Quebec but rather when he was called up by the Boston Bruins on Jan. 18, 1958 in a contest against the Montreal Canadiens. Willie O’Ree finished his NHL career with four goals and 10 assists, all during the 1960-61 campaign for the Bruins, and hung up his skates for good in 1979 after 21 professional seasons.

But it wasn’t glamorous for O’Ree. Willie had lost 90 percent of his vision in his right eye two years prior to his NHL call-up, which limited his playing ability severely, but nonetheless, he persevered and didn’t let anyone know of his impairment. In addition to his physical limitations, his physical appearance made things difficult throughout his career.

READ ALSO: Val James – The Forgotten Trailblazer

After breaking into the league in 1958, O’Ree expected that cheap shots would be coming. Included was an incident in Chicago where a player knocked out two of his teeth after calling him a derogatory name. The incident nearly led to a riot. In Willie’s eyes, the reaction from American fans was far worse than what he had received playing in Toronto and Montreal.

“Racial remarks from fans were much worse in the U.S. cities than in Toronto or Montreal,” O’Ree said. “I particularly remember a few incidents in Chicago. The fans would yell, ‘Go back to the South,’ and, ‘How come you’re not picking cotton?’ Things like that. It didn’t bother me. Hell, I’d been called names most of my life. I just wanted to be a hockey player, and if they couldn’t accept that fact, that was their problem, not mine.”

O’Ree made the first dent in the wall that had kept players of color out of the NHL, but it was the players after him that brought it to the ground. Val James, Bill Riley, and Mike Marson all came after O’Ree, but their impacts were limited. Tony McKegney put up a 78-point season for the St. Louis Blues in 1987-88, a record for black players until Jarome Iginla broke it in 2000-01 for the Calgary Flames. Edmonton Oilers legend Grant Fuhr, who is biracial, was the first black player to win the Stanley Cup when he did so in 1984.

Excellence is Universal

Fuhr was one of the best goalies in the NHL in the 1980s. From 1981 to 1990, Fuhr won 220 games for the Oilers (second only to Mike Liut), including five Stanley Cups (second all-time), one Vezina Trophy, and six All-Star teams. The opportunity he was given by his predecessors allowed him to barrel through the color barrier and shine for the whole hockey world.

While Fuhr dominated the 1980s, the next generation of black hockey players was waiting for their opportunities. Mike Grier, the first American-born and American-trained black hockey player to play in the NHL, began his career in 1996 for the Edmonton Oilers and would play 1,000 games in the NHL for four teams over the next 15 seasons.

Anson Carter, who started Big Up Entertainment in 2005, played 10 seasons in the NHL for eight different teams, compiling over 200 goals and over 400 points. Carter’s role as an analyst on NBC Sports and MSG Sports has helped open the door for other black hockey players to transition into a commentary role.

But it was Jarome Iginla who reached superstar status. Iginla played his first NHL game during the 1996 playoffs for the Calgary Flames, notching an assist in his first game. He became a regular for Calgary starting in 1996-97, finishing runner-up to Bryan Berard for the Calder Trophy for the league’s best rookie. Over 22 seasons, Iginla played for five teams and amassed 662 goals, 706 assists, and 1,138 penalty minutes between the regular season and playoffs.

The Changing Face of the NHL

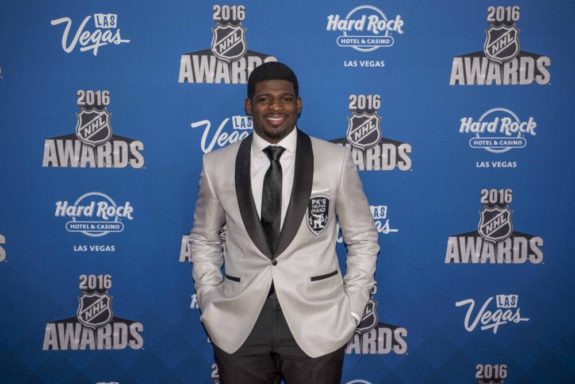

Iginla and Fuhr both reached superstardom in their own way, and in their own time, but the new generation could surpass them both. P.K. Subban is already a superstar; in nine seasons between Montreal and Nashville, he has 99 goals and 310 assists between the regular season and playoffs. In addition to his statistical success, Subban won the Norris Trophy for the top defenseman in the NHL during the 2012-13 season and was an All-Star Game captain at this year’s annual event.

Wayne Simmonds, similar to Subban in attitude and offensive prowess, has over 200 goals during his 10 years in the NHL, accompanied by a 2017 NHL All-Star Game MVP Award. Dustin Byfuglien, a 13-year veteran between the Chicago Blackhawks and Winnipeg Jets franchises, has a 2010 Stanley Cup championship and over 450 assists to his name.

With these established stars paving their own routes, the young prospects could follow them to success. Anthony Duclair, a third-round pick in 2013, already has posted a 20-goal campaign, and with the right change of scenery for the young forward, another 20-goal season isn’t out of the question.

Justin Bailey (Buffalo Sabres), Madison Bowey (Washington Capitals), Tyrell Goulbourne (Philadelphia Flyers), Josh Ho-Sang (New York Islanders), and Gemel Smith (Dallas Stars) all have the potential to be NHL stars, and with that level of excellence, could help spread the game to black neighborhoods in America and Canada.

But the NHL hasn’t been limited to black players emerging recently. Justin Abdelkader, whose family is of Jordanian descent, is the first Arab player to win the Stanley Cup. Nazem Kadri is Lebanese, Mika Zibanejad is Iranian, and Brandon Saad’s family is of Syrian descent.

Challenges Going Forward

Black players and other minority groups still face adversity both in the NHL and around the hockey world. While Willie O’Ree faced discrimination from both players and fans, many players today face a different challenge. They’re accepted by their teammates, coaches, and management, but many fans still choose to see them by their skin color.

In September 2011, in an exhibition game between the Detroit Red Wings and the Philadelphia Flyers, a banana peel was thrown at Wayne Simmonds while he was on the ice. In 2015, at a minor league hockey game in Rapid City, South Dakota, Native American children and teachers from a nearby reservation who were on a school trip were taunted by spectators and had beer thrown on them.

Hockey is still largely a white man’s sport (over 90-percent white), but in the last 20 years, the game has been changing. With stars such as P.K. Subban, Wayne Simmonds and Dustin Byfuglien enjoying exposure and success, young athletes have the opportunity to look up and idolize players who are like them, physically and in their experiences.

* originally published in Feb 2018

Enjoy more great hockey history and ‘Best of’ posts in the THW Archives

The post The NHL’s Evolution of Integration appeared first on The Hockey Writers.

Popular Articles

Blackhawks Chicago

Blackhawks Chicago Panthers Florida

Panthers Florida Penguins Pittsburgh

Penguins Pittsburgh Rangers New York

Rangers New York Avalanche Colorado

Avalanche Colorado Kings Los Angeles

Kings Los Angeles Maple Leafs Toronto

Maple Leafs Toronto Bruins Boston

Bruins Boston Capitals Washington

Capitals Washington Flames Calgary

Flames Calgary Oilers Edmonton

Oilers Edmonton Golden Knights Vegas

Golden Knights Vegas Flyers Philadelphia

Flyers Philadelphia Senators Ottawa

Senators Ottawa Lightning Tampa Bay

Lightning Tampa Bay Red Wings Detroit

Red Wings Detroit Islanders New York

Islanders New York Sabres Buffalo

Sabres Buffalo Devils New Jersey

Devils New Jersey Hurricanes Carolina

Hurricanes Carolina Stars Dallas

Stars Dallas Jets Winnipeg

Jets Winnipeg Blue Jackets Columbus

Blue Jackets Columbus Predators Nashville

Predators Nashville Wild Minnesota

Wild Minnesota Blues St. Louis

Blues St. Louis Mammoth Utah

Mammoth Utah Ducks Anaheim

Ducks Anaheim Sharks San Jose

Sharks San Jose Canucks Vancouver

Canucks Vancouver